Thoughts on the manifesto of futurist sacred art (1931)

The unfathomable fascination and blessed transparencies of the infinite.

Greetings to all readers and subscribers, and special greetings to the paid subscribers!

Please scroll down for the main topic of this newsletter. But first:

Mark your calendar! At the Terasem Colloquium on December 14, 2023, 10am-1pm ET via Zoom, stellar speakers will explore recent AI developments (ChatGPT & all that), machine consciousness, and the nature of consciousness. You are invited! Please note that a related issue of the Terasem’s Journal of Personal Cyberconsciousness (Vol. 11, Issue 1 - 2023) will be published in December. See the call for papers.

So far I’ve often linked to Wikipedia pages, but from now on I’ll link to Wikipedia much less, or not at all. Why? Because Wikipedia is politically and culturally biased. Politics doesn’t have much to do with what I write about, but culture does, and the two go together. What annoys me more in Wikipedia is that too many editors of science-related pages are dull bureaucrats of science and are always quick to label scientific theories they dislike as “pseudoscience” (whatever the fuck that means). So I’ll boycott Wikipedia and try to provide alternative references. Or just use Google, and skip the links to Wikipedia in the search results.

I often disagree with Kim Stanley Robinson, but he remains a great science fiction writer. I’ve been reading again “Galileo’s Dream” (2009), which I think is his best novel. Robinson masterfully mixes a well-researched and historically accurate (I guess) story of Galileo’s life after 1610 with a science fiction story in which Galileo is visited by time travelers from a future human society in the Galilean moons around Jupiter, and now and then abducted to their world. Robinson’s picture of multiple timelines as understood by future science is especially intriguing: “a manifold of different potentialities that interpenetrate and influence each other… a broad gravel riverbed with many braided channels, with the water running both upstream and downstream at once.”

I’m considering using the picture above in the cover of my next book “Irrational mechanics: Narrative sketch of a futurist science & a new religion.”

The picture shows a part of the painting “L’Adorazione” (The Adoration) by futurist painter Luigi Colombo, aka Fillìa. The painting is described in the Manifesto of futurist sacred art (in “Futurism: An Anthology,” 2009), by Fillìa and Marinetti, as

“a Madonna in prayer, whose body is dematerialized to the point where she is no longer recognizably human, an abstract form of prayer at the foot of a cross which is constituted solely by atmosphere.”

In his book “Trattato di Filosofia Futurista” (A Treatise on Futurist Philosophy), Riccardo Campa said that the publication of the Manifesto of futurist sacred art in 1931 (here is the original in Italian) marked the end point of a gradual erosion of the original anti-clerical identity of the futurist movement.

But I talked to Riccardo, who confirmed my impression that the Manifesto can also be seen as a call for a futurization of the church.

Fillìa and Marinetti say:

Sacred art should “completely renew itself through synthesis, transfiguration, dynamism, spatiotemporal interpenetration, simultaneous states of mind, and the geometric splendor of machine aesthetics…

Only Futurist aeropainters… can give plastic expression to the unfathomable fascination and blessed transparencies of the infinite… can make a canvas sing with the multiform and speedy aerial life of Angels and the apparitions of Saints…

Only Futurism, the insistent and speedy Beyond of Art, can shape and figure any Beyond life itself…”

The original text in Italian reads:

L’Arte Sacra dovrebbe “rinnovarsi completamente mediante sintesi, transfigurazione, dinamismo di tempo-spazio compenetrati, simultaneità di stati d’animo, splendore geometrico dell’estetica della macchina…

Soltanto gli artisti futuristi… possono esprimere plasticamente il fascino abissale e le trasparenze beate dell’infinito… possono far cantare sulla tela la multiforme e veloce vita aerea degli Angeli e l’apparizione dei Santi…

Il Futurismo incalzante e veloce Al-di-là dell’Arte, può solo figurare e plasmare qualsiasi al-di-là della vita…”

See also my “Thoughts on the manifesto of futurist science (1916)” with a longer commentary on futurism and Riccardo’s book.

See also Marinetti’s late work “L’aeropoema di Gesù” (1943-44) with a thoughtful commentary (in Italian) on the Manifesto of futurist sacred art.

I look forward to seeing an interpenetrating, futurized synthesis of science and religion, and to experiencing the blessed transparencies of the infinite in futurist sacred art (and science).

Fillìa was also a leading exponent of aeropainting, an artistic movement that by “an absolute freedom of imagination… captures the immense visionary and sensual drama of flight.” The quote is taken from the Manifesto of aeropainting (in “Futurism: An Anthology,” 2009), authored by Fillìa and other futurist artists.

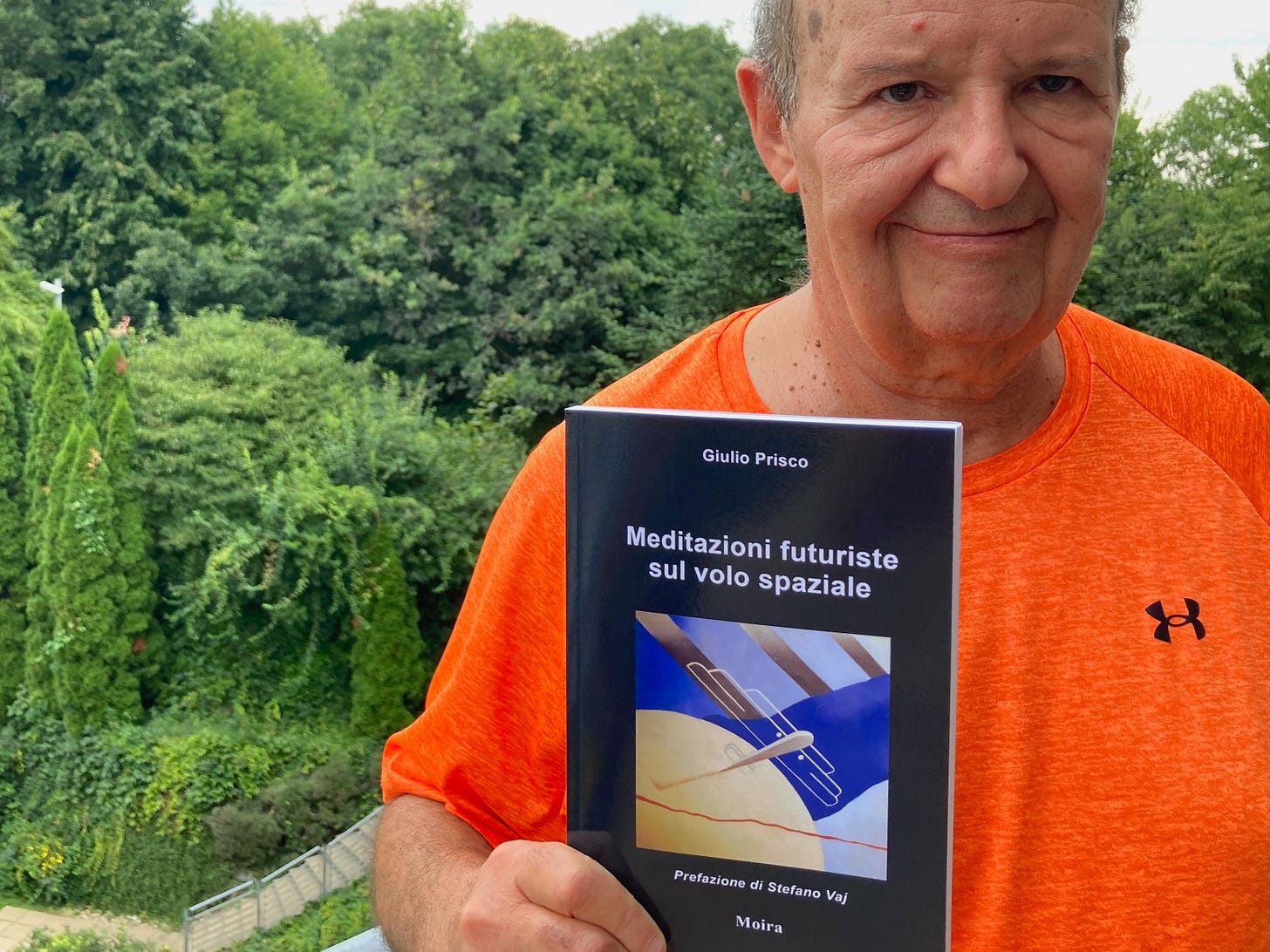

I’ve used another painting by Fillìa, “Mistero aereo” (Aerial mystery) in the cover of the Italian translation of my spaceflight book: “Meditazioni futuriste sul volo spaziale” (2023). In this recent interview with futurist Roby Guerra (in Italian) I talk about the book and spaceflight, or course Elon Musk, and many related things including futurism and Turing Church.