The Artist of universe programming

Donald Knuth on God and computer science.

Greetings to all readers and subscribers, and special greetings to the paid subscribers!

Please scroll down for the main topic of this newsletter. But first:

Come and listen to my talk for Space Renaissance next week on Feb. 19, 7pm CET (1pm ET).

I’ll elaborate on the cultural issues discussed in my book “Futurist spaceflight meditations” (2021). Then I’ll discuss the long term future of space expansion and elaborate on its spiritual implications. I promise a blunt and provocative talk, with the gloves off. Here’s a little teaser.

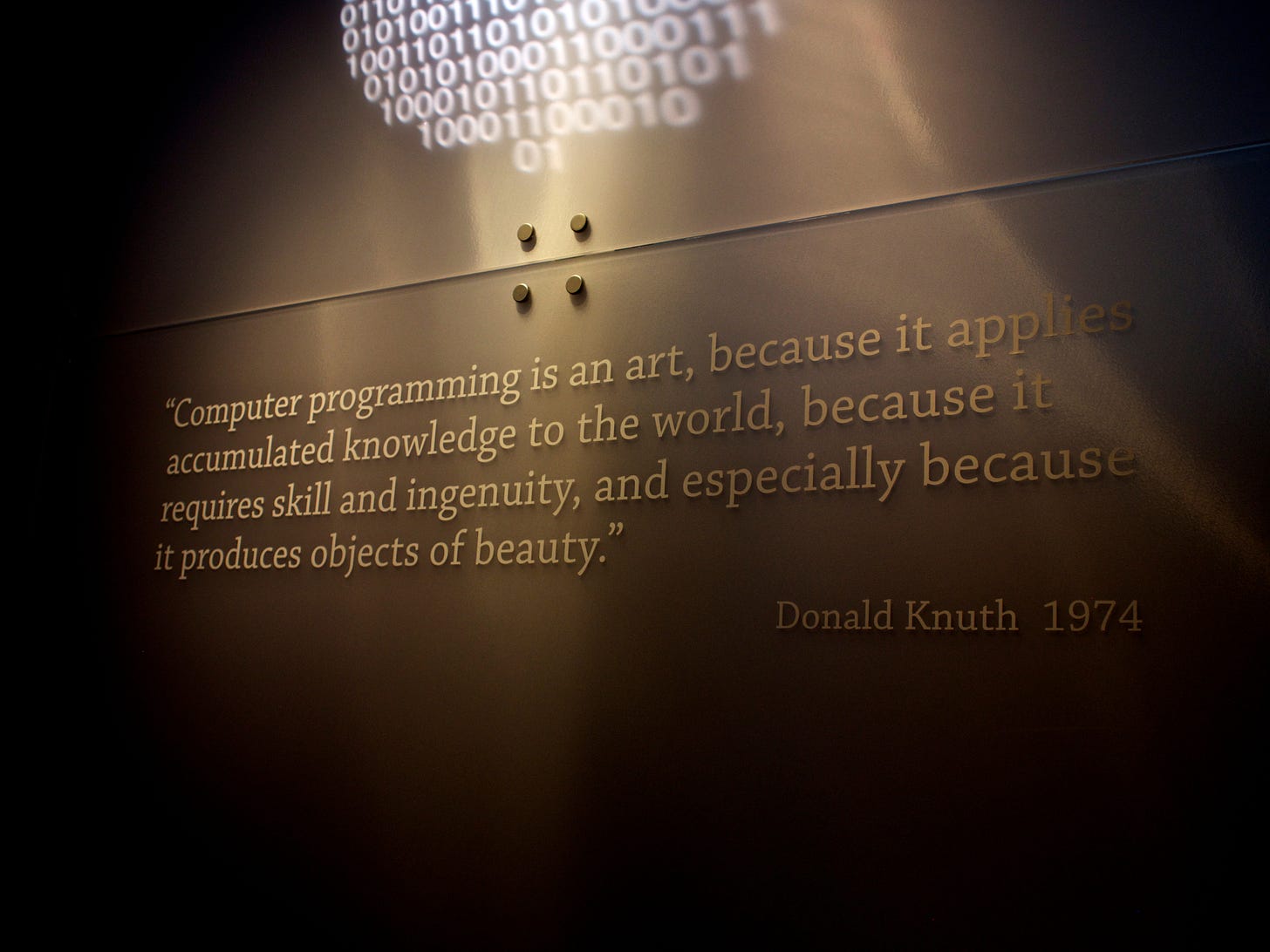

Donald Knuth is the legendary Professor Emeritus of The Art of Computer Programming at Stanford University, and the author of the equally legendary “The Art of Computer Programming” (and many other books).

The best you can do to get to know Knuth is watching two episodes of Lex Fridman’s podcast (1, 2). Lex Fridman produces great one-on-one interviews with the most interesting thinkers around.

One of Knuth’s other books, titled “Things a Computer Scientist Rarely Talks About,” contains transcripts of six public lectures given by Knuth at MIT in 1999 on faith and science, edited and annotated by the author. You can also listen to the audio recordings of the lectures.

“In this series of six spirited, informal lectures, Knuth explores the relationship between his vocation and his faith, revealing the unique perspective that his work with computing has lent to his understanding of God.”

Yes, strange as it may seem to the politically correct bureaucrats of science, Donald Knuth is a deeply religious person.

The lecture I found most interesting is the last, titled “God and Computer Science.” Here are some short excerpts that I found especially interesting. I’m collecting and annotating them here because some of these concepts and quotes must find their way into my book in progress.

“God can know much more than enough, and can be plenty powerful enough, to do anything relevant to the universe, without being strictly all-knowing or all-powerful. Finiteness is not a limitation in practice.”

I agree. Any being that is powerful enough would be an entity that we could only call a God.

“Well, the fact is, real numbers are an abstraction, an idealization. I grant you that they’re an immensely useful abstraction: The concept of real numbers allows us to apply calculus and other tools of mathematics to solve all kinds of important problems. But it’s a tremendous leap of faith to assume that real numbers apply perfectly to the real world…”

Very good point, see Nicolas Gisin’s work.

“Einstein made a famous comment that ‘God doesn’t play dice with the universe,’ and he held to that position for the last thirty years of his life. But nowadays that’s definitely a minority opinion… computer scientists have proved that certain important computational tasks can be done much more efficiently with random numbers than they could possibly ever be done by any deterministic procedure… If Einstein’s assertion were true, God would be prohibited from using the most powerful methods.”

Count on Knuth for making good points that seem obvious after you here them! If God does anything that can be thought of as computation (or as I’m more inclined to say, if God IS some kind of computation), then of course God would use the most powerful computational methods.

“we can think of God as a tree pruner, occasionally influencing the outcome of various branches while simultaneously adjusting the nonobservable information behind the scenes so that all observations remain consistent with quantum mechanics. And we ourselves - even us, our spirits or souls or minds or whatever you want to call this part of our being - we might be little tree pruners too, with much more limited and local powers, of course, but still able to exercise free will in this way.”

This is very similar to my own ideas, inspired among others by Rizwan Virk who also uses similar language.

“Dorothy Sayers said that she enjoyed writing plays better than writing novels, because the actors and actresses would reveal deeper meanings that she hadn’t specifically planned.”

So perhaps God puts us on the scene to play the script in the hope that we improvise and make the script better?

“There is good reason for a thousand people to work on a problem even though only one of them is going to solve it, and even though the people know in advance that only one of them is going to influence the final answer.”

Yes! All those people contribute to achieving a critical mass of overlapping and interacting ideas for a solution that, eventually, will enable one lucky person to find a good solution. This is a great motivational talking point: do your best, and you’ll be part of the solution. On the very speculative side, if Rupert Sheldrake is right, even just thinking about something can influence others through morphic resonance.

“I noticed debates in the faith and science community about ‘top-down causality’ versus ‘bottom-up causality.’ I thought I might point out that my research on so-called attribute grammars shows that top-down and bottom-up causality can coexist quite nicely. But I never had time to explore that in depth.”

This is the most interesting point, and I’m trying to wrap my head around it. “Programming Language Pragmatics” (2015) is the clearest reference on attribute grammars that I’ve found, and cites Knuth’s original works. I see the analogy and I’m thinking about what exactly it says.