Irrational mechanics, draft Ch. 8

The cosmic operating system.

Greetings to all readers and subscribers, and special greetings to the paid subscribers!

Please scroll down for the main topic of this newsletter. But first:

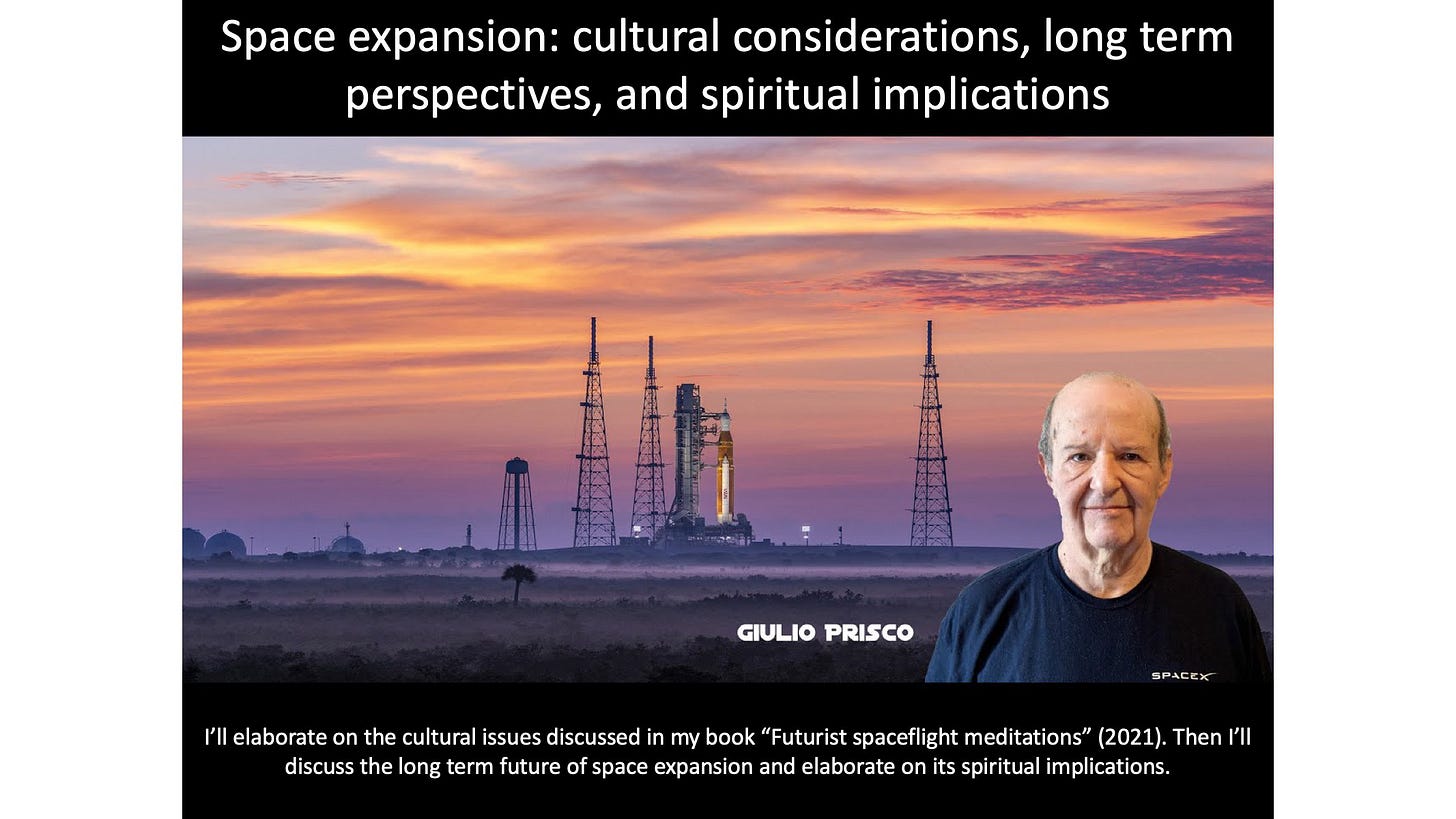

Come and listen to my talk for Space Renaissance on Feb. 19, 7pm CET (1pm ET). I’ll elaborate on the cultural issues discussed in my book “Futurist spaceflight meditations” (2021). Then I’ll discuss the long term future of space expansion and elaborate on its spiritual implications. I promise a blunt and provocative talk, with the gloves off.

In the meantime, listen to recent Space Renaissance talks by Remo Rapetti and Frank White.

So here’s a very early draft of Chapter 8 of my new book “Irrational mechanics: Narrative sketch of a futurist science & a new religion” (2024).

I have split Chapter 4 in two (4 and 5), so Chapter 5 is now 6 and Chapter 6 is now 7.

Note that this and the others draft chapters are very concise. At this point I only want to put down the things I want to say, one after another. Later on, when the full draft for early readers is complete, I’ll worry about style and all that.

8 - The cosmic operating system

I’ve repeatedly hinted at this something that I’m calling the cosmic operating system. Now I’ll try and say something more.

The program that computes the universe doesn’t determine what happens here from what happens nearby and what happens next from what happens now, but rather imposes global rules upon the whole universe of space and time [Chapter 4, 5]. The global rules are global constraints that select certain possible states and histories (timelines) of the universe.

I guess the global rules include thermodynamics, but also more complex and very complex rules related to the emergence of life and consciousness, and to the ultimate destiny of all timelines. Perhaps even rules related to the elusive Quality that inspired Robert Pirsig [Chapter 7]. Emily Adlam [see Chapter 4] thinks, she told me, that this could well be the case. More or less anything one can imagine could be written in the form of a constraint, she said, so the key problem is to come up with some criteria for how we should judge whether a putative constraint is really part of the objective structure of reality.

Richard Feynman was open to the possibility that, in our quest for the ultimate laws of physics, we could find out that “it’s like an onion with millions of layers” [Feynman 2005], and so am I. Actually, I think this is the case indeed. Peel one more layer of the cosmic onion, find some more laws, and you still have millions of other layers to peel and millions of other laws to find. So there are simple rules and then more complex rules, and then even more complex rules and so forth, and more and more new laws that combine and interfere with, or supersede, the old ones.

At each step, the cosmic operating system looks less like a simple little program and more like a complex, giant mind. Borrowing the words of James Jeans, “the universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine.” [Jeans 1930].

“I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists,” said Albert Einstein [Jammer 1999], “not in a God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings.” In other words, Einstein’s God is not a personal God but the impersonal laws of physics.

If the laws of physics are simple then, using the language of computer scientists, everything is determined by a simple program. The simple program works more or less like this: take an arbitrary initial state of the world, and follow its evolution in time with simple dynamical laws that fit on a t-shirt. Run the simple program and congratulate yourself if it produces useful results. If not, blame the arbitrary initial state and try to adjust it.

But what if the laws of physics are hugely complex, with all sorts of rules and constraints piling up and interfering? If so, the simple program becomes an unfathomably complex operating system, much more complex and intelligent than any Artificial Intelligence (AI) that we can build or even conceive at this moment. The cosmic operating system is a giant mind that thinks about a lot of things, perhaps including life and consciousness, perhaps even including the fates and actions of individual human beings, and acts with free agency and intelligence.

I’ll also refer to the cosmic operating system by other names.

One other name is Mind at Large, a term introduced by Aldous Huxley [Huxley 1954, 1956]. Huxley hinted at “the totality of the awareness belonging to Mind at Large” and the perception, by Mind at Large, “of everything that is happening everywhere in the universe.” I’m agnostic on Huxley’s claim that psychedelic drugs can expose users to Mind at Large, but I think the idea of a universal Mind makes a lot of sense. I’ll use the term Mind at Large when I want to emphasize the mind-like aspects of the cosmic operating system.

But you may be thinking that you already have a perfectly good name: perhaps you call the cosmic operating system God, or God by any other name. That is, you identify Mind at Large with the personal God(s) of your religion. If the cosmic operating system is a superintelligent Mind that oversees and steers the whole of reality, then you can call it a God, why not. What more can you want from a God? To me, this is God.

Interestingly, more and more people are taking the habit of speaking of the universe where their grandparents would speak of God. This linguistic habit, which is becoming commonplace, seems to suggest that our collective mind is warming up to new conceptions of the divine [Chapter 15].

I’ve introduced the concept of Mind at Large, the intelligent universe that thinks and acts, as another name for the cosmic operating system. That is, Mind at Large doesn’t live in a specific physical substrate, but is just another name for the ultimate laws of physics that move the atoms and the stars, operating like a giant AI.

This concept may seem too abstract and difficult to grasp, but it might grow on you if you think of it. If not, there are more tangible pictures of a universal mind.