Strange consciousness: Stanisław Lem

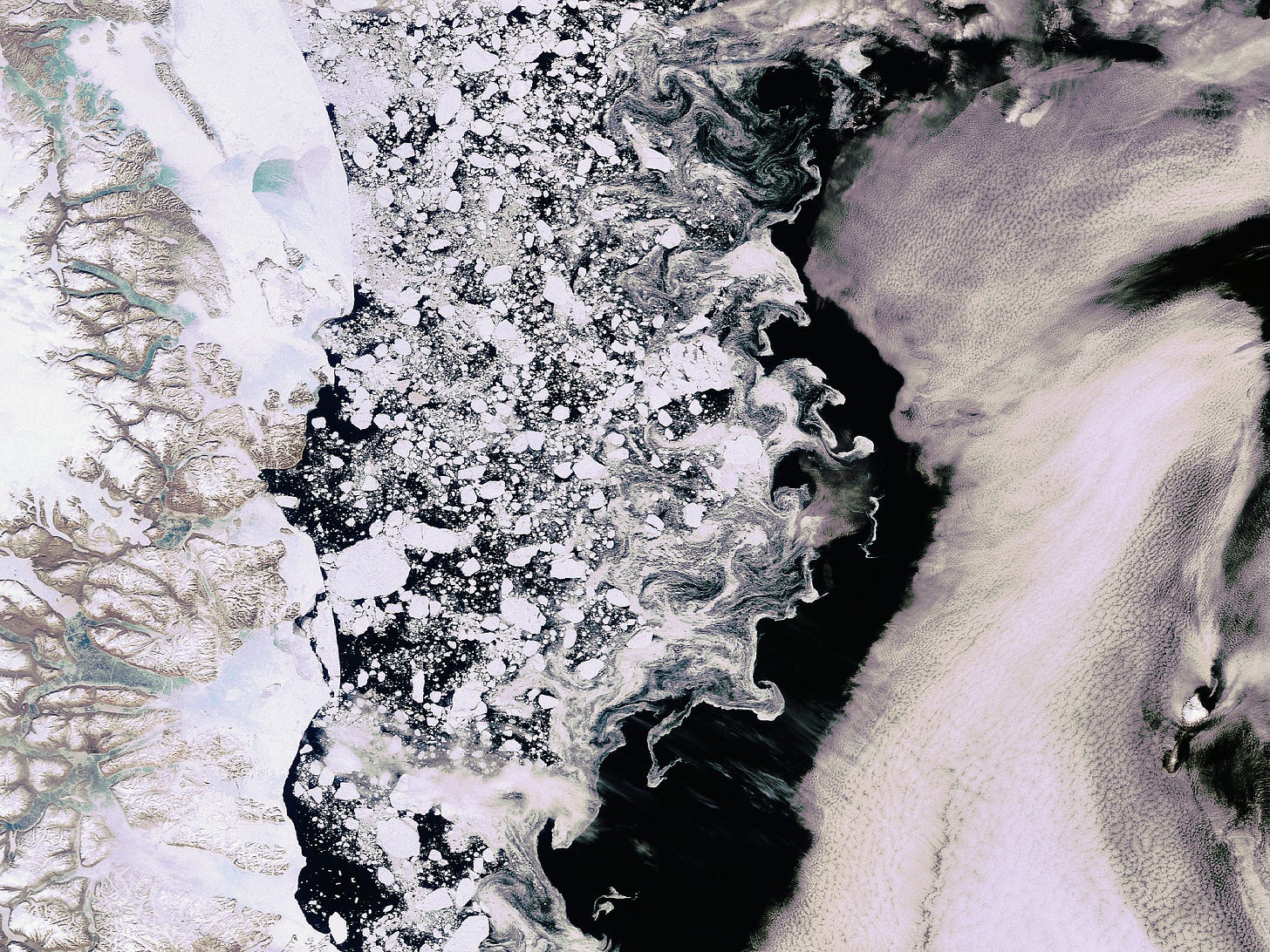

Future superintelligent AIs could look & feel like the ocean of Solaris.

Greetings to all readers and subscribers, and special greetings to the paid subscribers!

Please scroll down for the main topic of this newsletter. But first:

Ben Goertzel & friends have organized a Beneficial AGI Summit & Unconference in Panama City, Feb. 27 - Mar. 1 2024, + online. See Ben’s post.

Here’s the BGI Pre-Event Series Kick-off video, with Ben and Ibby Benali.

Other speakers will follow in the pre-event series. In the video description there are links to social media channels. At this moment Ben’s GREAT book “A Cosmist Manifesto” (here’s a free PDF) is trending in the social channels.

Progress in Artificial Intelligence (AI) is accelerating, and the related e/acc philosophy is becoming controversially popular. We could see human-level AIs any day now, and then superintelligent AIs much smarter than us.

Thomas Nagel suggested that forms of alien consciousness could be “totally unimaginable to us.” The consciousness of future AIs is likely to be very alien to us and very difficult to imagine. But we’ll have to live with AIs, perhaps soon, and then with very powerful superintelligent AIs. Good science fiction and good philosophy written by great science fiction writers help us imagine what they could be like.

My favorite mental picture of a very alien consciousness is the powerful living ocean in the science fiction masterpiece “Solaris” [Lem 1970], by Stanisław Lem. Lem leaves open the possibility that the apparently intelligent behavior of the ocean could be nothing more than the unthinking metabolism of a very alien life form, but also the possibility that the ocean could be a superintelligent being with a very strange form of consciousness.

Lem constantly reminds us that the operation of mindless physics could be indistinguishable from conscious intelligence. To me, this means that perhaps physics is not mindless. More soon.

To Lem, who doesn’t make a sharp separation between natural and artificial processes, machine personality “will be as different from human personality as a human body is different from a microfusion cell” [Lem 2013].

I’m republishing here two 2014 essays: “Stanisław Lem’s Summa Technologiae portrays a grim and sober singularity” and “Lem’s strange aliens, revisited,” with some typos and links fixed.

These essays analyze some of Lem’s fiction (“Solaris” - “His Master’s Voice” - “The Invincible”) and non-fiction works (“Summa Technologiae”).

In the essays below I discuss the well known film adaptations of “Solaris.” More recently I watched on Netflix the film “Az Úr hangja” by Hungarian filmmaker György Pálfi, inspired by “His Master’s Voice.” The film is half in Hungarian and half in English, with the Hungarian part subtitled. I don’t find the film on Netflix anymore, but there’s a copy on YouTube (not HD and without subtitles).

The film is not an adaptation of Lem’s book but an experimental film inspired by and loosely connected to the book. I didn’t expect a close film adaptation, so I wasn’t disappointed and liked the film. But I would like to watch a close film adaptation because “His Master’s Voice” is a masterpiece of philosophical science fiction and one of my favorite science fiction books ever. Pure Lem, as good as “Solaris.”

The 2020 edition published by MIT Press has a foreword by Seth Shostak. In Shostak’s words, Lem offers “a deeper look at what would follow an actual SETI detection” and “deftly anticipates the inevitable ambiguities, the personal conflicts, and even the inescapable government paranoia.”

The discovery of a SETI signal might “change from fiction to fact tomorrow” and “offer an opportunity to glimpse the incandescent wisdom of intelligence millions or billions of years more advanced than ourselves.”

Stanisław Lem’s Summa Technologiae portrays a grim and sober singularity

Stanisław Lem’s Summa Technologiae was first published in 1964 in Poland. Now, some 50 years later, the publication of the English translation by Joanna Zylinska is finally making Lem’s thoughts about science, technology, and the future accessible to Western readers.

Lem, who passed away in 2006, is known and loved by science fiction readers worldwide. With more than 25 millions books sold, he may be the most widely read science fiction writer ever, which shows that there has always been a demand for mature, complex science fiction literature.

A common theme in Lem’s fiction is the strangeness, fundamental incomprehensibility of alien intelligences out there (see “Lem’s strange aliens, revisited” [*]). The lesson is that alien intelligences may be so different from us, their consciousness so alien, with textures and flavors so different from our own consciousness, that communication may prove impossible. Lem warns not to anthropomorphize - the universe is probably stranger than we imagine, perhaps stranger than we can imagine.

A common message emphasized in Lem’s science fiction, especially in his works of the ‘60s, when Summa was published (for example in Solaris, The Invincible, and His Master’s Voice [*]), is that our human intelligence, consciousness, our particular human way to inhabit the universe, may be overrated - other life forms may be more efficient and more powerful than us without being sentient in any sense that we can understand, and natural phenomena (not even life forms, just mindless matter and energy following natural laws) may exhibit behaviors similar to conscious intelligence. With this persistent uncertainty between sentience and automation, life and non-life, Lem warns that reality may be stranger than our current models.

In Summa Technologiae, Lem shows the science and possible future technologies behind his fiction. The title of this sprawling book, which means “Sum of Technology” in Latin, alludes to Summa Theologiae, the title of the 13th century compendia of theology written by Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus. Lem’s Summa Technologiae, surprisingly actual despite its age, explores themes found in later science and fiction, including virtual reality, synthetic biology, nanotechnology, artificial life, artificial intelligence, life in the universe, evolution, the future of humanity and technology, transhumanism, and Lem’s own grim, sober concept of technological singularity.

I think if Summa had been translated to English immediately after publication, some of the neologisms coined by Lem for technologies that didn't exist at the time would be still used today. So Google would do “ariadnology” (a guide to the labyrinth of the already assembled knowledge), virtual reality would be “phantomatics,” neuroscience would be “cerebromatics,” and artificial intelligence would be “intelectronics.” In all cases, Lem imagines developments more advanced than today’s technology – for example phantomatics and cerebromatics provide full stimulation of all senses via direct neural interfaces with instant feedback loops, influencing mental processes while bypassing afferent neural pathways, and intelectronics achieves consciousness and intelligence amplification in machines.

The overall scope of the book can be categorized as cybernetics, a term very much in vogue in the ‘60s but not used much these days, defined by Norbert Wiener as “the study of control and communication in machines and living beings.” In other words, “cybernetics examines structure and stability in groups of organisms: how they evolve in order to establish homeostasis, and what communication methods the organisms use to maintain homeostasis,” writes David Auerbach in his review of Summa.

“Loosely speaking, cybernetics is an abstracted, unified conception of evolution and artificial intelligence.”

Homeostasis, the process of constant adaptation of a system to its environment, with feedback loops that regulate both system and environment, is a central concept in cybernetics. Some homeostats have a “‘second-order regulator,’ that is, the brain, which - depending on the situation - is capable of changing the ‘action plan’ (‘self-programming via learning’).”

I recommend to read also Peter Swirski’s A Stanislaw Lem Reader (1997), with more recent interviews and Lem’s reflections on Summa Technologiae 30 years after its first publication. “I regard Summa Technologiae as a remarkably successful book, in the sense that so much of what I wrote there has in the meantime come true,” says Lem in 1992. “Today I am able to discern the reason for the rather considerable accuracy of my predictions,” says Lem in the essay “Thirty Years Later” (in Swirski’s book). “Quite simply, my general assumption was a conviction that life and the processes examined by the biological sciences will become an inspirational gold mine for future constructors in all phenomena amenable to the engineering approach.”

Summa is full of references to the blind efficiency of biological evolution, which often finds optimal solutions. “When it comes to their capacity, throughput, degree of miniaturization,” says Lem in the conclusion of Summa, “economy of material, independence, efficacy, stability, speed, and last but not least, universality, chromosomal systems manifest superiority over brain ones.”

Lem begins with a comparative analysis of the evolution of biological and technological systems, focusing more on the similarities than the differences. Both biological and technological systems are homeostats constantly engaged in feedback loops with their environment, which for technological systems includes their creators, and for some biological systems (e.g. humans) includes technology. I think if Lem wrote Summa today he might use the evolution of mobile phones as an example: the shape and features of mobile phones evolve under environmental pressure (performance of chips and screens, consumer reactions) and influence us in turn (just look at teens). At this moment the result is the typical smartphone running iOS, Android or Windows Phone (which also invaded the niche of other technologies such as consumer cameras and camcorders), but mobile technology is still evolving fast and I guess it will reach equilibrium when phones/computers will be directly implanted in the brain (Cerebromatics!), which may happen by the end of next decade.

“Perhaps we will eventually gain a kind of longevity that will practically amount to immortality, but to do this, we will have to give up on the bodily form that nature gave us,” says Lem. Discussing the future of humanity, he often plays with the concepts and ideas of transhumanism, and formulates his own sober, grim concept of technological singularity:

“The point is not to construct synthetic humanity but rather to open up a new chapter in the Book of Technology: one containing systems of any degree of complexity. As man himself, his body and brain, all belong to such a class of systems, such a new technology will mean a completely new type of control man will gain over himself.”

Such powers, however, are not likely to be achieved with simple extensions of today’s technologies. “Even if we ourselves choose the end point, our way of getting there is chosen by Nature. We can fly, but not by flapping our arms… [Machine] personality will be as different from human personality as a human body is different from a microfusion cell. We can expect some surprises, problems, and dangers that we cannot even imagine today.” This is similar to Vinge’s concept of technological singularity as a point in history after which things become impossible for us to imagine. Lem talks of highly imaginative super technologies, including “cosmogonic engineering,” the creation of artificial worlds inhabited by sentient creatures:

“[Imagine] a large, complex system the size of ten Moons that is a homeostatic pyramid consisting of closed, descending feedback systems. It resembles a digital machine that is self-repairing, autonomous, and self-organizing… [The processes] are capable of producing an intelligent personality and sentient senses.”

Lem is not a transhumanist or a singularity enthusiast ante-litteram. If anything, he suspects that future generations may lose interest, like we lost interest in the transmutation of elements envisaged by alchemists, which could be done with today’s technology but is not considered worth doing. At the same time, Lem thinks that almost everything is possible, with one important exception: our descendants will never decide to “let things be the way they are now; let them remain like this forever.”

A very interesting chapter is dedicated to the search for other civilizations in the universe, and why we don’t see evidence of “miracles” built by advanced civilizations, which according to Dyson and Kardashev should be able to build marvels of astro-engineering that can be detected across the Galaxy. Lem formulates a possible explanation: perhaps the paths of different civilizations diverge wildly after a certain point, and only a few civilizations remain interested in space exploration and astro-engineering. Lem thinks, however, that the universe is probably full of alien civilizations.

What forms of consciousness shall our descendants find out there? More generally, what forms of thinking life are possible, including sentient artificial life that could be created in the future? Here, like in his science fiction, Lem warns not to anthropomorphize - sentient life may be more similar to the living ocean in Solaris [*], or the self-organizing swarms of micro-robots in The Invincible [*] than to our intuitive anthropomorphic models. Lem thinks that “we are inclined to overestimate the role of intelligence as a value in itself,” and we should “refrain from turning the ‘gravitation toward intelligence’ into a structural tendency of evolutionary processes.” In the chapter on constructing consciousness, he writes:

“If the fact that x is conscious is only determined by the behavior of this x, then the material from which it is made does not matter at all. It is therefore not just a humanoid robot or an electronic brain but also a hypothetical gaseous–magnetic system, with which we can have a chat, that belongs to a class of systems endowed with consciousness… [The] brain surely is not the only possible solution to the problem of ‘how to construct an intelligent and sentient system’… As long as only birds or insects could fly, ‘flying’ was equivalent to ‘living.’ Yet we know too well that devices that are completely ‘dead’ are also able to fly today. It is the same thing with the problem of intelligence and sentience.”

In conclusion, I highly recommend this classic of scientific imagination, enjoyable and thought-provoking, sometimes outdated but surprisingly actual nonetheless.

[*] See this older post:

Lem’s strange aliens, revisited

I started 2014 reading the recently published English translation of Stanisław Lem’s masterpiece Summa Technologiae (see my forthcoming review “Summa Technologiae – Lem’s grim, sober Singularity”), so I decided to revisit some of Lem’s science fiction works.

Lem, who passed away in 2006, is known and loved by science fiction readers worldwide. With more than 25 millions books sold, he may be the most widely read science fiction writer ever, which shows that there has always been a demand for mature, complex science fiction literature.

A common theme in Lem’s fiction is the strangeness, the fundamental incomprehensibility of alien intelligences out there. The lesson is that alien intelligences may be so different from us, their consciousness so alien, with textures and flavors so different from our own consciousness, that communication may prove impossible. Lem warns us not to anthropomorphize - the universe is probably stranger than we imagine, perhaps stranger than we can imagine. Lem’s novels often leave the reader in a moody state of quiet despair. I prefer more positive, solar science fiction, but this is Lem, one of the greatest writers and thinkers of the 20th century. Who am I to criticize him?

In Solaris, Lem’s best known work, scientists face a strange, utterly alien living ocean, that fills a planet around a double star. The ocean is clearly alive, its behavior resembling the muscular activity of an organic being, or perhaps the neural activity of a giant brain. It creates huge and incomprehensible structures of jelly and hardened foam, larger than cities, which are cataloged but never understood by the scientists.

Perhaps the living ocean is incomparably more intelligent than us, and it is certainly much more powerful: it can tweak the laws of physics within its strange creations, control and stabilize the orbit of the planet around the double star, and even fabricate persons out of subatomic matter, from memories extracted from the minds of the scientists. These “guests,” perhaps emissaries, perhaps sensors, weapons, or perhaps even gifts, seem fully conscious and able to understand that they are not real persons, which results in a deeply moving tragedy. The scientists can communicate with the guests, but never with the ocean itself, which is probably sentient but with a consciousness so different from ours that communication will remain impossible. The guests, the persons fabricated by the ocean, are able to communicate and show human feelings – they pass the Turing test. But the ocean itself doesn’t, and perhaps its apparently intelligent behavior is really the unthinking metabolism of a very alien life form.

I watched again two film adaptations (1972 and 2002) of Solaris. Both are good films, but fall short of the book. Both films emphasize the tragic love story between man and ghost more than Lem intended, with a “happy end” (sort of) in the 2002 film. Lem writes: “to my best knowledge, the book was not dedicated to erotic problems of people in outer space… in “Solaris” I attempted to present the problem of an encounter in Space with a form of being that is neither human nor humanoid.”

In both films I miss the majestic swirls, contortions and creations of the living ocean.

In His Master’s Voice, scientists study a message received from the stars, encoded in neutrinos. Narrated in first person after the facts, His Master’s Voice is really a long philosophical essay, with just enough story telling to keep the reader’s attention (the book is one of the very few philosophical essay that I know of which is also a page-turner). The project, narrated by a participant – a famous mathematician – in a memory found after his death, takes place in a closed government facility, and of course there are plans to exploit the findings for military applications.

A part of the message seems understandable, and the scientists find a way to use it to synthesize a new material with strange properties, perhaps a new life form sent from the stars. But the purpose of the new material is never understood, the rest of the message never decoded, and the goal of the project – decoding a message sent by an alien civilization – is muddled by more and more uncertainties. Perhaps the message is not a message at all, but radiation based on unknown science, broadcast to stimulate the emergence of life in the universe. Perhaps the signal is not even the work of intelligent aliens, but the outcome of unknown natural phenomena, perhaps related to residual radiation leaks between phases of a cyclic, expanding and contracting universe. But is there always a meaningful difference between the actions of intelligent life and the “mindless” works of the laws of physics? The question is left unanswered, and the signal from the stars remains a Rorschach test, onto which we project what is in our own minds.

In The Invincible, the crew of a starship landed on an apparently desert planet must confront highly efficient self-organizing swarms of insect-like, self-reproducing, self-repairing micro-robots, apparently evolved over the ages from war robots left by a civilization that visited the planet long ago. The micro-robotic swarms are the survivors of the evolutionary struggle for the survival of the fittest, and the masters of the planet. Though probably not sentient in any sense that we can relate to, the swarm intelligence of the robotic insects proves more much effective than ours, and the human cosmonauts must retire in defeat after many losses.

A common message emphasized in all three books is that our human intelligence, consciousness, our particular human way to inhabit the universe, may be overrated - other life forms may be more efficient and more powerful than us without being sentient in any sense that we can understand, and natural phenomena (not even life forms, just mindless matter and energy following natural laws) may exhibit behaviors similar to conscious intelligence. With this persistent uncertainty between sentience and automation, life and non-life, Lem warns that reality may be stranger than our current models.

The way I see the neuronal ocean planet Solaris is that it's a living being, not AI, although it becomes when its creatures are born from memories/data, but when it's not copying from existing models, the creations are more freeform and also often useless in reality, when not trying to communicate -- for example with the humans studying it --, although beautiful to be seen by those witnessing the phenomena on Solaris. Thank you for this article about Stanislas Lem!